Our Work

No organism exists alone. Bacteria, no matter where they live, must cope with the presence of huge numbers of other bacteria competing for the same space. Animals are coated, both in and out, with complex communities of microorganisms. Sometimes these interactions benefit one or more of the partners, and become stable in evolutionary time: they become symbioses. We are interested in how and why symbioses form, how they are maintained, and what happens as the associations become more and more intertwined.

We work with a number of study systems, including sap-feeding insects and their (unculturable) endosymbiotic bacteria, Drosophila cell lines and whole flies, and various culturable bacteria. Occasionally, when someone brought the right expertise to the lab, we've worked with plants, beetles, fungi, and lichens. We use an evolutionary perspective with a variety of approaches—cell biology, biochemistry, genomics, genetics, and field biology—to address our questions.

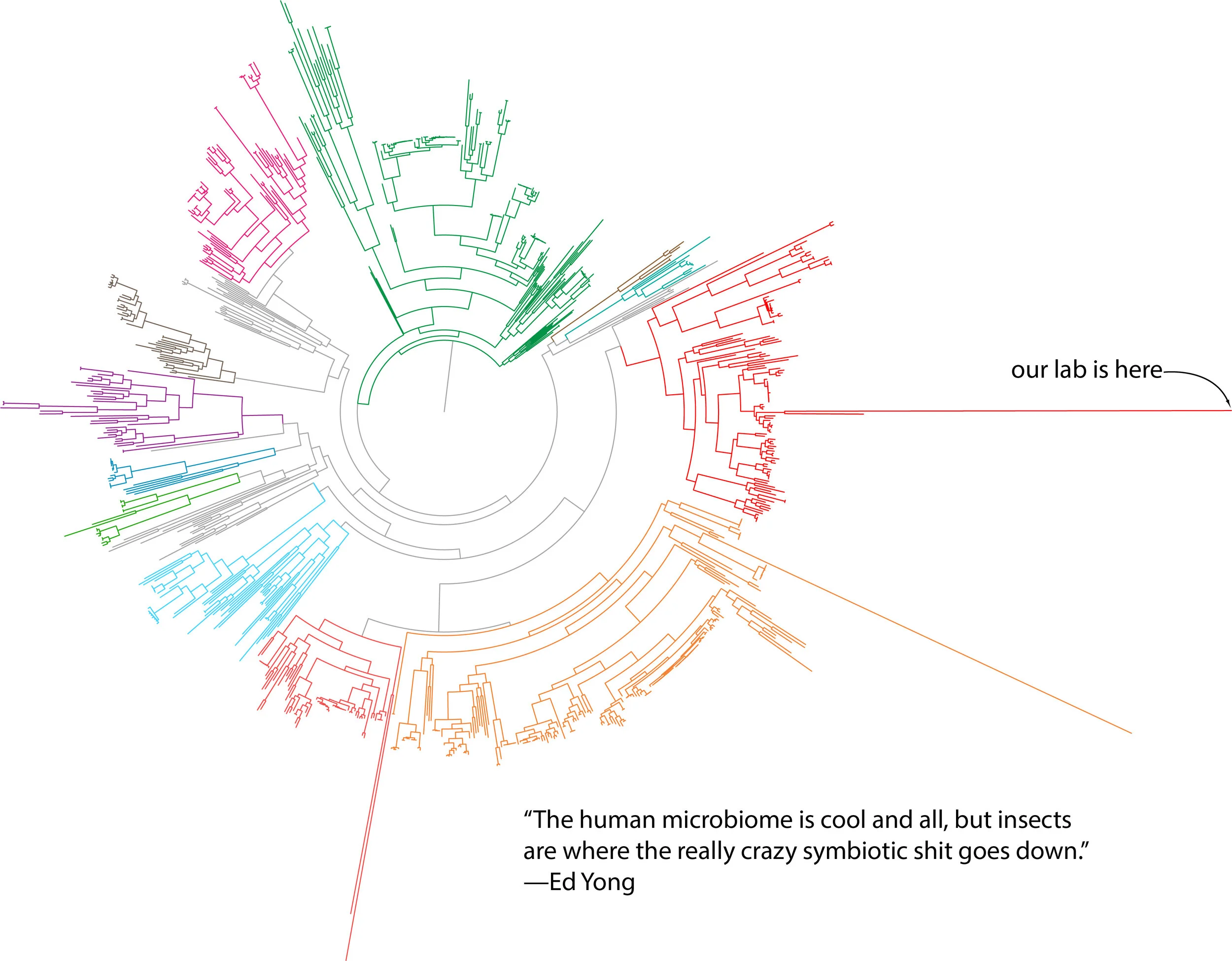

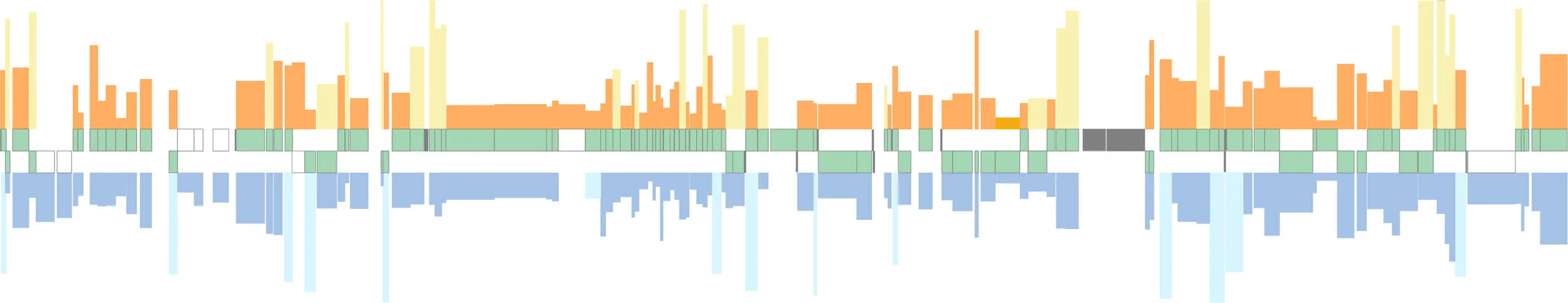

Genome Instability in Endosymbionts

When a bacterium becomes an endosymbiont, its genome loses genes and gets smaller. In most cases, bacterial endosymbionts that become stably associated with their hosts have genomes that become very small and very stable. While genome stability remains the most common outcome, our work on cicadas in particular has shown that genome stability is not always the outcome of long-term symbiosis. We first reported that one endosymbiont of cicadas, called Hodgkinia, had fractured into two new lineages by an unusual 'speciation' event (Van Leuven et al., 2014, Cell). These two new lineages had each lost genes in a complementary way that left each new lineage dependent on the other. We went on to show that the splitting frequency was likely related to the lifecycle length of its host insect (Campbell et al., 2015, PNAS), and that different cicada species showed various amounts of Hodgkinia splitting (Łukasik et al., 2018, PNAS). We found that the longest-lived cicadas had Hodgkinia populations that had not two, or three, or even ten, but more than 40 distinct Hodgkinia lineages in single insects (Campbell et al., 2017, Curr Biol). We suspected that this process was non-adaptive, or even maladaptive for host insects. We have been able to show one possible cost to this process, where the host tissue that houses Hodgkinia must expand in size to accommodate these new lineages, at a cost to the cicada's other bacterial symbiont, Sulcia (Campbell et al., 2018, mBio). Finally, in collaboration with our colleagues Yu Matsuura and Takema Fukatsu, we have been able to show that some cicadas, presumably to get around the cost of splitting in Hodgkinia, have replaced Hodgkinia (but not its partner symbiont, Sulcia) with a previously pathogenic fungus (Matsuura et al., 2018, PNAS).

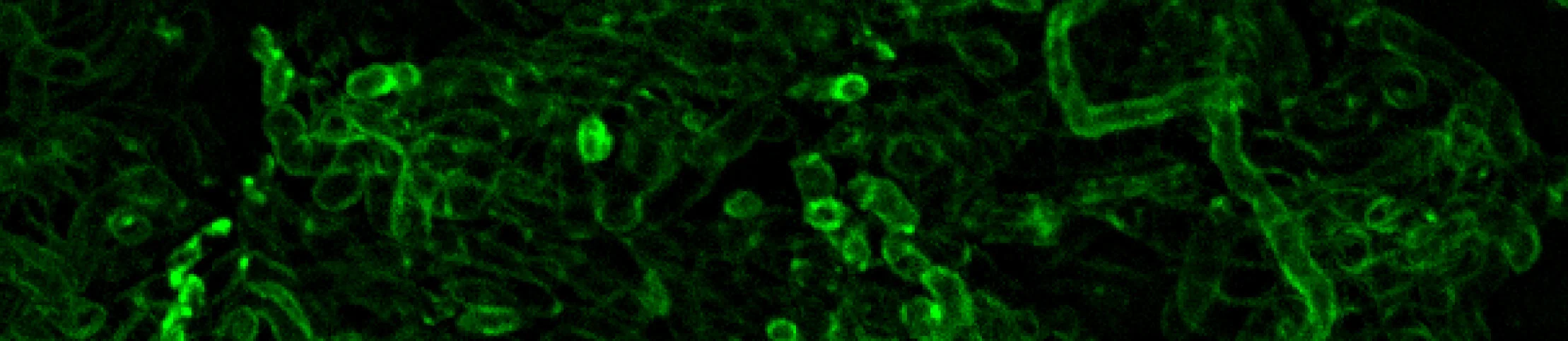

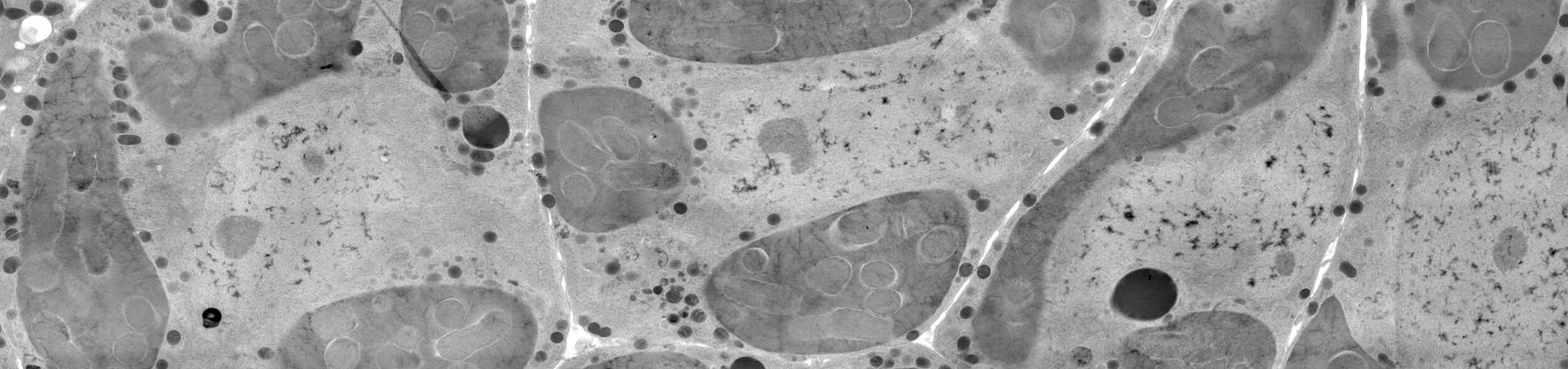

Functional Integration Between Endosymbionts and Host Cells

The tipping point for when an endosymbiont 'becomes' an organelle has been debated for years, and many definitions have been proposed. We use the symbiosis between mealybug insects and their bacterial endosymbionts as a proxy for the process of organelle formation. The interesting thing about mealybugs is that one of the endosymbionts, Moranella, lives inside of the cytoplasm of the other bacterial endosymbiont, Tremblaya. This type of prokaryote-in-prokaryote structure is extremely rare in biology and is likely to have been involved in the origin of the eukaryotic cell itself.

We first showed that Tremblaya had fewer genes than any other non-organelle endosymbiont (about 120 protein coding genes), and that many biochemical pathways in Tremblaya were genetically intertwined with those from Moranella (McCutcheon and von Dohlen, 2011, Curr Biol). Inspired by the way organelles function, we next sought to find whether or not Tremblaya or Moranella genes might have been transferred to the host insect. We found that, indeed, dozens of bacterial genes were present and apparently functional on the insect genome, except none seemed to be from Tremblaya or Moranella (Husník et al., 2013, Cell). These horizontally transferred genes were from extinct bacterial infections. We spent six years developing complex experiments to prove whether this genetic mosaic was actually functional. In 2019, we finally proved that this patchwork does indeed work, and that at least some horizontally transferred genes make proteins in the host insect which are specifically transported back into Moranella cells (Bublitz et al., 2019, Cell). This paper shows that the mealybug endosymbionts are 'organelles' by any previously proposed definition.

The Difference Between Old and New Endosymbionts

Most of the endosymbionts our lab studies are old: they have been living in insect cells for tens to hundreds of millions of years. We focus on these systems on purpose, because we are interested in how old endosymbionts become integrated with their host cells, and how this integration might teach us something about mitochondria and plastid evolution. But we also work at the other end of the spectrum, on bacteria that have recently become established as endosymbionts. We are trying to figure out how these new partners adapt to their new co-symbionts, and how the mechanisms used in newly established relationships might be related to mechanisms used in ancient relationships. Which genes are easily lost in endosymbiosis, and which stick around longer? How does the process of becoming an endosymbiont affect gene expression and protein production in the new endosymbiont?

The Host Processes Involved in Endosymbiont Integration

Little is known about the mechanisms host cells use to form stable cell biological interactions with their endosymbionts. Which parts of the host cell are important for establishment and maintenance of an intracellular bacterium? What components of the host endomembrane system are used in housing and transmitting endosymbionts? How do host genes, both native and those acquired through HGT, work to maintain endosymbionts? We are using CRISPR, RNAi, proteomics, immunohistochemistry, transcriptomics, and electron microscopy to address these questions.

Other Things?

Active projects in the lab are mostly focused on the ideas presented in this review and this review. If you are interested in this kind of stuff, or maybe are thinking about joining the lab, please contact us!